Speed Summary: Empathy

- Empathy: Why it Matters, and How to Get it

- Author: Roman Krznaric

- Publisher: Rider

- Publication: 2015

In Empathy – Why it Matters and How to Get it, the founder of the world’s first Empathy Museum Roman Krznaric summarises a decade of research into the art, science and practice of empathy, our ability to step into the shoes of another person and see the world through their eyes.

Krznaric is a founding faculty member of the School of Life, and his exposition of empathy is clear, compelling and captivating. But where Empathy really shines is in offering practical advice for using empathy at home, at work and in research. So if you want to skip the introduction and jump straight to how to create empathy experiences and participate in empathy training, click here.

What is Empathy?

Empathy is a personality trait that refers to our ability to feel and understand what someone else is experiencing. Empathy is part of our social intelligence.

Our ability to empathise has two components:

- Affective empathy’ is automatic emotional mirroring, our involuntary (System 1) tendency for our emotions to converge with those expressed by others.

- ‘Cognitive empathy’ is deliberate perspective-taking, our conscious (System 2) capacity to imagine what it must be like to be someone else.

Together, the two components of empathy allow us to project ourselves into the shoes of another and experience the world from their perspective.

Wired for Empathy

Although the term empathy is a relatively new word, coined by American psychologist Edward Titchener in 1909 (adapted from the German word Einfühlung (‘feeling into’), empathy itself appears to be built into human nature and the evolved neurobiology of our brains.

- We have mirror neurons, discovered by neuroscientist Giacomo Rizzolatti in 1992, that fire both when we experience an emotion and when we experience someone else experiencing an emotion. Highly empathic people may have more mirror neurons.

- Our brains include a complex ‘empathy circuit’ comprising at least ten interconnected regions, including mirror neurons, as revealed by research psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen.

- Neuroeconomist Paul Zak has researched a HOME circuit (Human Oxytocin Mediated Empathy) in the brain, which triggers a release of the neurochemical oxytocin when we see someone in distress, prompting caring and helping behaviour.

Krznaric shares evidence that our cognitive (deliberate) capacity for empathy, also called ‘theory of mind’ develops through childhood. For example, children under four cannot complete the ‘3 Mountains task’ proposed by psychologist Jean Piaget in 1948. The task involves asking what a doll would see from different vantage points on a model mountain. The ability to ‘shoe-shift’ and see the world from someone else’s perspective kicks in at about five years of age.

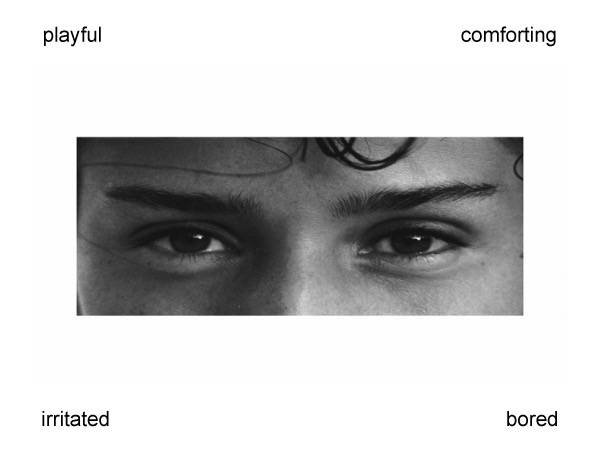

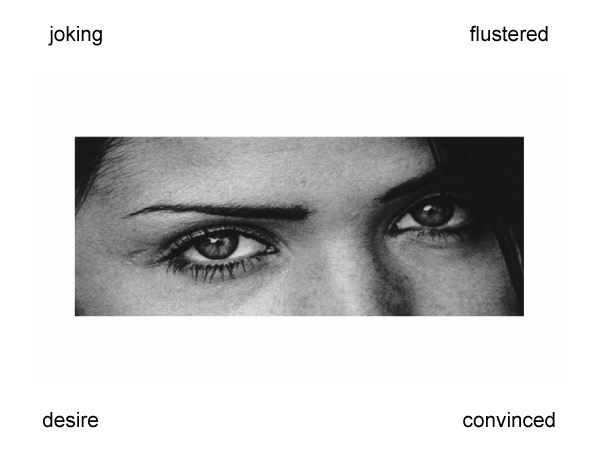

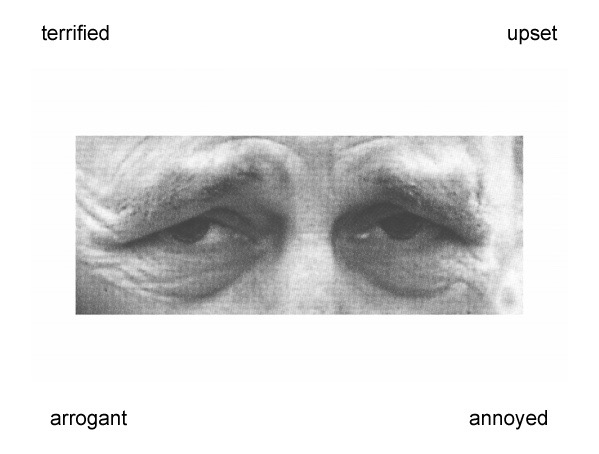

Finally, Krznaric notes that like many other human abilities, people’s empathic capacities can vary. Just as there are IQ tests to measure IQ there are empathy tests such as the ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ test that can measure your empathic capacity (our empathy abilities appear to be linked to our ability to read people’s emotions from their eyes). Some of us may have more empathy (women tend to have more), and some less. But apart from an estimated 2% of the population who are either psychopaths, brain damaged, or suffer from severe autistic disorders, we all have some capacity to empathise with others. Empathy is human nature.

Empathy Test: Can you tell what these people are feeling?

Why Empathy Matters

Krznaric argues that our ability to empathise with others is a core driver of human social connection and bonding. Without the ability to step into the shoes of another, we would not understand each other, nor would we feel the bond of common humanity that can motivate us to care for and help each other.

With empathy,

The book draws on the insights of psychologist Steven Pinker, suggesting that our capacity for empathy has flourished since the enlightenment and has been one of the major causes in the decline in torture, slavery, and persecution. According to wellbeing scholar Richard Layard, we all share the benefits of cultivating empathy because empathy promotes caring, and the more we care about other people, the more likely we are be happy ourselves.

The Empathy Deficit

However, Krznaric argues that empathy is under threat today. For example, a meta-analysis of student empathy test scores in the US found a 40% decline in empathy levels between 1980 and today. President Obama has gone on record suggesting that the world is suffering from an empathy deficit:

“There’s a lot of talk in this country about the federal deficit. But I think we should talk more about our empathy deficit – our ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, to see the world through those who are different from us…”

Barack Obama

Krznaric suggests that human empathy has been undermined by the cult of the self which is being amplified by mobile technology and social media.

- Parenting, education and therapy culture have all sought to help our fragile sense of self to thrive and flourish in a challenging world. Self-esteem, self-belief, self-respect, self-determination, self-reliance, self-actualisation, and even self-love can all be seen as essential to human wellbeing. Be that as it may, this cult of the self – as embodied by the self-esteem movement – can promote introspection and self-focus, rather than ‘

outrospection ‘ and a focus on the other. So rather than face facts, we may follow our feelings, be true to ourselves, but in doing so, cut ourselves off from others. - Mobile technology and social media may be exacerbating the empathy deficit. Empathy evolved to flow in face-to-face situations, as a form of automatic non-verbal communication. As digital communication displaces or replaces face-to-face communication, the flow of empathy may be compromised. For example, behind the anonymity and invisibility of the mobile screen, we can become susceptible to the ‘online disinhibition effect’, and feel free to engage in antisocial and aggressive behaviour such as cyberbullying. Moreover, as the mobile screen becomes a remote control for life, our sense of self-importance and self-centricity may be bolstered as we command the world by simply tapping or swiping for cabs, delivery, movies, sex and love. Social media may play a role in amplifying this self-centricity by rewarding self-promotion and self-aggrandisement, whilst personalising news and information to reinforce our personal biases and prejudices. By eroding viewpoint diversity, social media may build polarisation, reinforce stereotypes and encourage prejudice as we amplify perceived ‘social distance’ between ‘us’ and ‘them.

How to Build Empathy

Where Krznaric’s book becomes most interesting is in proposing practical things to flex your empathic muscles and boost your empathic capacity.

These empathy-building tools fall into two basic categories; empathy experiences and empathy training

1. Empathy Experiences

The gold standard way to step into the shoes of another and experience the world from their perspective is to literally do just that – step into their shoes and experience what they are experiencing first hand for yourself.

The great pioneers of empathy research did exactly this

- Beatrice Webb, a Victorian social reformer, went undercover in 1887 to experience what it was like, first-hand, to be a sweatshop worker in Victorian London. Her four-day immersive empathy experience resulted in a magazine article ‘Pages from a Work-Girl’s Diary’ that caused a public sensation, leading to a testimony of to her findings at a House of Lords Select committee.

- George Orwell, the novelist, went undercover in 1927 to experience what it was like, first-hand, to be homeless and down and out in Paris and London. His multiple underground excursions lasted weeks at a time, and his empathy experience resulted in the book Down and Out in Paris and London.

- John Howard Griffin, the investigative journalist, went undercover in 1959 to experience what it was like, first-hand, to be an African-American in the deep south of the US. Not an African American himself, Griffin died his skin black with pigment-darkening medication, and spent six weeks travelling and working in Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia and South Carolina. His empathy experience was published in the book ‘Black Like Me’, which has since become a standard textbook on college syllabi.

- Günther Wallraff, the German investigative journalist, went undercover in 1983 to experience what it was like, first-hand, to be an immigrant Turkish worker in West Germany. His two-year undercover immersive empathy experience was published as Lowest of the Low in 30 languages, selling over two million copies.

- Patricia Moore, the designer who has been called ‘the mother of empathy’, went undercover between 1979 and 1982 to experience what it was like, first-hand, to experience life as an elderly woman. Working with a professional make-up artist, she transformed herself wearing clouded glasses that blurred her vision, earplugs that partially deafened her, and splints, braces, and bandages to reduce movement. Her experiences in the kitchen resulted in the easy-open cereal packs and the OXO Smart-Grip range of kitchen utensils. Empathic experiences do not always involve becoming someone else, if you are the target market – Moore used empathic design (using feelings as an indicator of underlying needs and expectations) to redesign a

mammograph with an automatic quick-release mechanism to minimise discomfort.

For Krznaric these empathy research pioneers revealed that first-hand immersive experience is the high road to building empathy. To empathise with your customer, you need to experience yourself what it is like to be your customer.

If it is not possible to step into the shoes of another with whom you wish to empathise, Krznaric proposes a number of other empathy experiences.

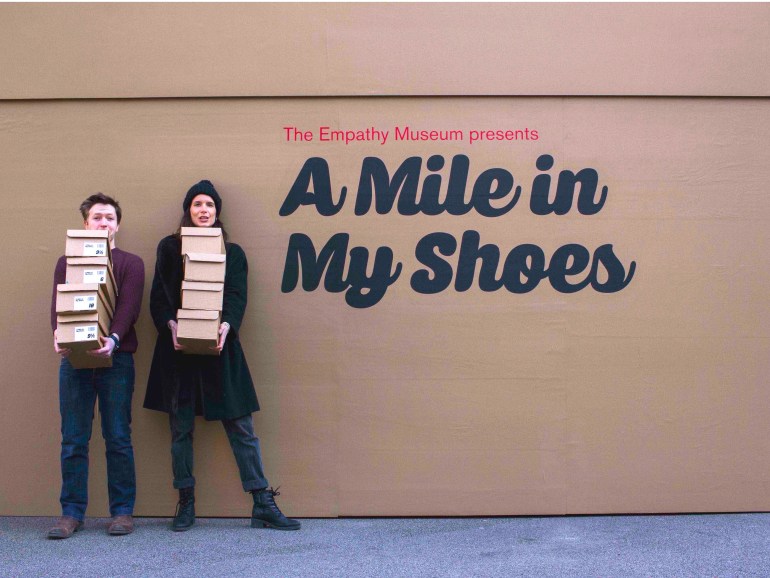

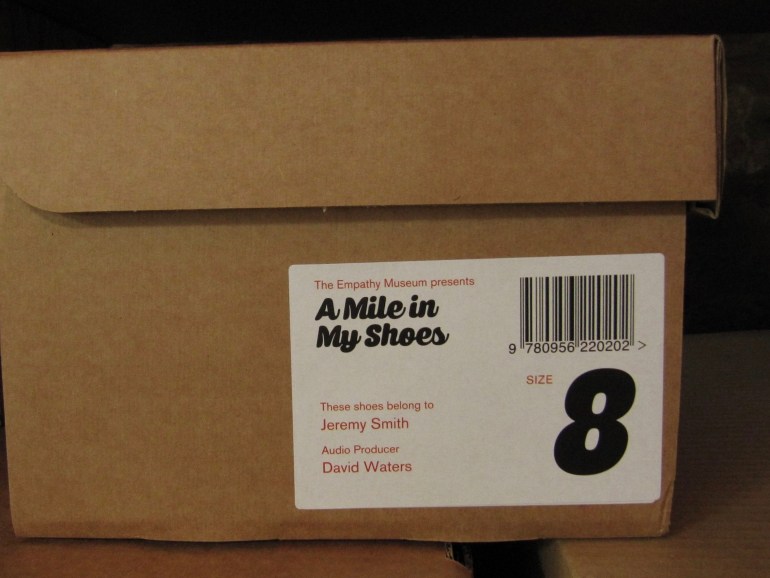

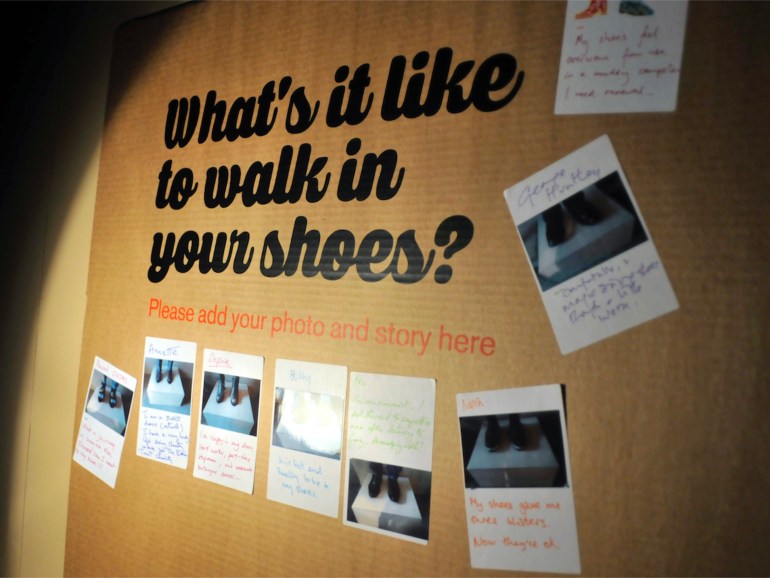

- Empathy Museum. Now launched, Kriznaric shares an empathy experience that became a giant pop-up shoebox that visitors enter to borrow a pair of shoes and walk a mile wearing them, whilst listening to a podcast of the owners’ personal experience. Kriznaric suggests that an Empathy Museum could be expanded to include acting lessons and to help people discover the secrets of stepping into the life of another person, a dressing up box to get into character, an empathy café that shows the people behind the food you are eating, a human library – where you borrow a human who has

first-hand experience during the visit to bring the museum to life, and empathy tests withneuro-imaging to find out your empathy levels. - Empathy Conversations. Also launched in various guises, empathy conversations are another empathy experience designed to help people divided by difference to connect personally and share experiences. For example, The Parents Circle is an initiative designed to facilitate conversations, understanding and dialogue between families in Palestine and Israel who have lost family members in the conflict. One such initiative is the ‘Hello Peace’ telephone line, with a free phone number that encourages families to reach out and get to know someone from the other side. Over a million calls have been made on the Hello Peace line since it was set up in 2000. Other empathy conversations include ‘Conversation Menu’ sessions, such as those run at the School of Life. Conversation Menu sessions are the opposite of speed-dating and involve strangers meeting over a menu of conversations prompts served with simple food and designed to foster empathy through the sharing of personal experiences. Kriznaric suggests that “we need to become empathy gardeners, seeding millions of shoe-swapping conversations in school rooms, board rooms and war rooms, in pubs, churches, kitchens and online”.

The Award winning roving Empathy Museum

2. Empathy Training

In addition to promoting empathy experiences such as first-hand empathy immersion, empathy museums/events, and empathy conversations, Kriznaric suggests we could all benefit from empathy training to boost our empathic capacity. This could build on existing empathy training run for healthcare professionals and mediators, and empathy training that is increasingly offered in schools

- E.M.P.A.T.H.Y training.

Dr. Helen Reiss has developed, tested and validated a simple empathy training solution for boosting empathic capacity among healthcare professionals based on an E.M.P.A.T.H.Y. mnemonic. This involves facilitating eye-contact, focusing on facial muscles of the other, posture, affect (emotional expression), hearing the whole person, and being mindful of your own emotional and physiological response. In tests, empathy training improved ability to decode empathic signals, and improved patient perception of physician empathy (as measured by the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure (CARE) of empathy). - NVC Empathy training. Psychologist Marshall Rosenberg developed an empathy training method to help mediation in personal, organizational, and political settings. Known as NVC (non-violent communication), the NVC approach involves focusing expressed emotions of the other to diagnose their underlying needs (‘receiving empathically’), and then sense-checking understanding with them in neutral, non-evaluative language ‘so you feel x, because of y?’. Independent reviews of NVC empathy training have found NVC associated with positive outcomes in mediation.

- Empathic Perspective-Taking training. Psychologists Adam Galinsky and C. Daniel Batson have tested and validated possibly the simplest method to boost your empathy. Simply practice deliberate perspective-taking. This simply involves imagining what it must feel like to be someone else. Make a conscious effort to either imagine their experiences and feelings or to imagine a day in their life, looking at the world through his eyes and walking through the world in his shoes. In experiments, deliberate perspective-taking led to increased empathy.

- Roots of Empathy Training. Developed by empathy activist Mary Gordon in 1995, Roots of Empathy is an evidence-based school program dedicated to promoting emotional literacy and empathy among children aged 5-13. The program is centred around a local parent and infant who visit a class with an empathy instructor every three weeks over a year. The children are taught how to recognise and identify the infant’s emotions, and then read their own and their classmates’ feelings. In controlled tests in Scotland, Roots of Empathy training led to

55 % increase in sharing and helping behaviour among pupils. In England, a parallel Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) programme for primary and secondary school children has been established which includes empathy training tasks such as filling in ‘thought bubbles’ in photo stories to help young people recognise what other people are thinking and feeling.

The BG Take

What a book! For any innovator or market researcher, Empathy offers practical ideas and inspiration for how to use empathy as a research technique to better understand people and their needs.

Using empathy training techniques, qualitative researchers can open the flow of automatic affective empathy and hone their deliberate perspective-taking cognitive empathy skills.

And by adopting empathy experiences as a research technique, clients and researchers can help bridge the empathy gap to better understand the feelings and needs of the people who buy their products and services.

We believe human empathy is an essential tool in the qualitative researcher’s toolbox for three reasons.

- First, empathic research can help qualitative researchers spot new insights and opportunities that may be invisible to quantitative research. The human capacity for sharing emotions and perspective taking is something that no quantitative analysis can replicate (yet).

- Second, empathic research can help researchers interpret quantitative data by illustrating the people behind the numbers. In a world where quantitative data and research automation can flatten human experience to numbers and algorithms, empathic research can help humanise quantitative research and bring quantitive data to life

- Third, empathic research can boost the impact of market research to drive change in an organisation. As pioneers in empathy research found, empathic research inspires change by provoking an empathic response in the audience, emotionally moving and motivating people to care.

Ultimately, in a world where the role of qualitative research is challenged by quantitative data analytics, the power of empathic research lies in its ability to make us care.